Not a good start but consistant, it’s been less than 6 months since my last post. At some point I do want to stick to a consistant frequency in blog posts, I’m not sure what that frequency will be, but the desire is there. I have been busy of course with gradschool and considering life’s progress. All things considered, I am in a relativly good place and making progress in the contemplation of which of many possible paths to follow. Since removing myself from volunteer obligations, I hanen’t realy been involved in anything outside of school and home. The academy has been my world since August 2023. So, lets dig into some details.

My B.S. in Religion took longer than it should have, 2018-2021. I stepped up my game for the M.A. in History and completed it in four terms, 2021-2023 amidst some distractions early on. The M.A. in Public History started in the spring 2024 term and will be completed in the fall of 2024. I am almost half way through the second master’s now, just three more weeks to go. Off loading the mass of volunteer work helped tremendously in finishing the first M.A. and diving right into the second. With three more classes to go, I am raring to get these knocked out by the end of the year. An Internship, a Local Historical Research class, and a Digital History class are what is left to complete.

As I plan for the next phase, I need to start narrowing my interests in the field, at least for the dissertation phase of the doctoral path. Yes, the decision to pursue a terminal degree in history has been made, more or less… ??? Yes, I know, is it a yes or is it a no, the variable is employment. I am activly looking for a remote adjunct in history position at the undergraduate level. If I can find one that requires less than 20 hours a week I should be able to take that on and work on the Ph.D.. In broad terms, Industrial Revolution (IR) technologies is a vast span of material to cover, far too broad for a dissertation. Trying to narrow the scope has been dificult since I haven’t had the time do any in depth reading or research to narrow things down to a tight topic. My other academic interests skirt history proper so they also play into the process. Political science, industrial archaeology, experimental archaeology, and experimental history all have a place in the field.

Along with the lack of time to attack the mountain of reading material to find a narrow topic for a dissertation, I also have some academic challenges. I am a slow reader. I read for context and understanding. I have a tendancy to wander on concepts in the reading, and when I come across a word I am not familiar with I look it up. When there is reference to a person, movement, or concept I am not familiar with, I need to divert my attention to understand the context. This can slow things to a frustratingly glacial pace.

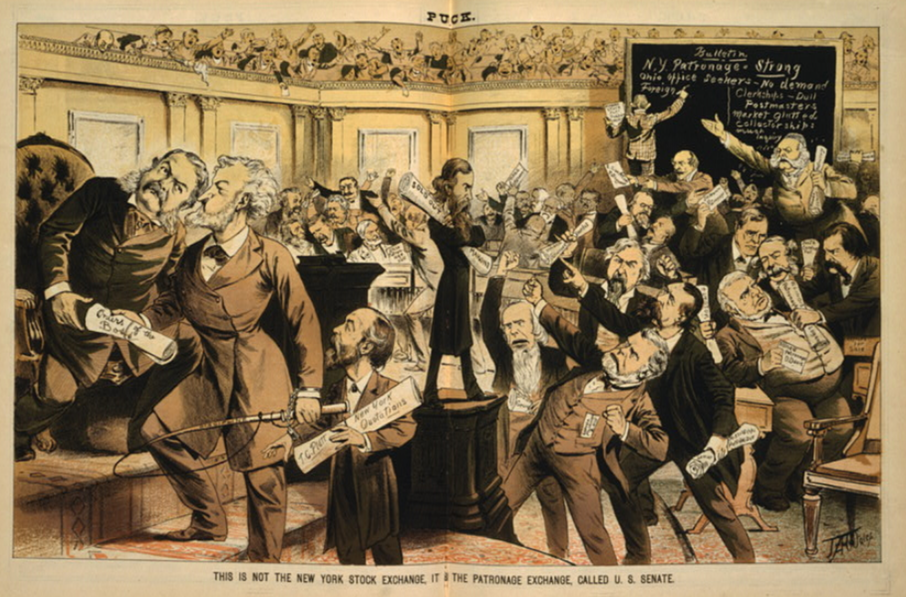

As an example, I am currently indulging my political science and history interests on fascism in America and Europe toward the end of the IR. Klemperer’s The Language of the Third Reich1 is literally about the contextual language of the Reich, which is German. I don’t speek or read Greman. I can work out some of the pronunciations and word forms but I want to have at least a cursery understanding of the proper pronunciation, structure, and context so that when these words come up in research in various texts, and they do, frequently, I want to grasp the actual meaning. German words appear in English translations mainly because linguisticly German creates compound words that translate to sentenses in English, with meaning often beyond the litteral translation. This matter is compounded by the context of when the expanded word came into common use, when common meaning changed, or when it left common usage.

Volk [people]2 is the stating point for a plethera of other words, Volkswagen, is people’s car in a general context. In the context of 1930s Germany, volk means folk which has a nuanced context that might not be understand without a German language background as well as the period context of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei [National Socialist German Workers’ Party]. Thus in a 1938 text with Volkswagen, the car of the folk takes on a different context and meaning. This is only one of many words in the volk family which were used to great effect in propaganda and the building of a fictional “historical” Nordic narrative.

I have a number of books on the shelf waiting to be read. Most can be placed into one of four main categories. Late-19th to mid-20th century fiction which is important for contextual interpretation, the civil rights movement and elements there of, facsism and democracies, and architecture. A broad swath of topics but they all relate to history and public history. There is also a backlog of more reading material on my wishlist. This is another of the reading issues, so many things to read but I have to keep my time reserved for academic works first. This will be even more critical in the second phase of the doctoral path, the comprehensives. Anything tangential will have to wait at least until the dissertation phase.

If I do manage to find the unicorn of employment over this summer or fall I will need to start considering a dissertation question and thesis, I will also need to start thinking about publish or parish. There are a number of forms to consider, journal articles, papers, reviews, books, and documentaries. These will also benefit from a narrowing of the field. As I get closer to a question and thesis, I should be able to take some of the impractical side topics uncovered in the dissertation research and pursue them for publication. Time to start looking at journal submission criteria.

Until next time,

~Jon Wanzer, M.A.